10 March 2023

![]() 5 mins Read

5 mins Read

I have crossed the Northern Territory’s East Alligator River and gone deep into Arnhem Land.

Cahill Crossing along Alligator River. Aptly named because of its crocodile population. Located in the Arnhem Land region of NT.

Now, sitting on a sandstone ledge at Mount Borradaile, I gaze at a mulberry red Tasmanian devil with jagged teeth underneath a large yellow sting ray. Nearby are two punishment spearings and a rainbow serpent creation ancestor. I can scarcely believe I am one of the few people to have seen this art since its rediscovery.

Davidson’s Arnhem Land Safari’s senior guide Clare Wallwork and her partner Roger Johnsson discovered these art-filled shelters just last year.

Today, their excitement is still palpable as we walk along the escarpment pocked with the dogged roots of fig trees and spiky pandanas palms. A lime green wetland stretches to the horizon.

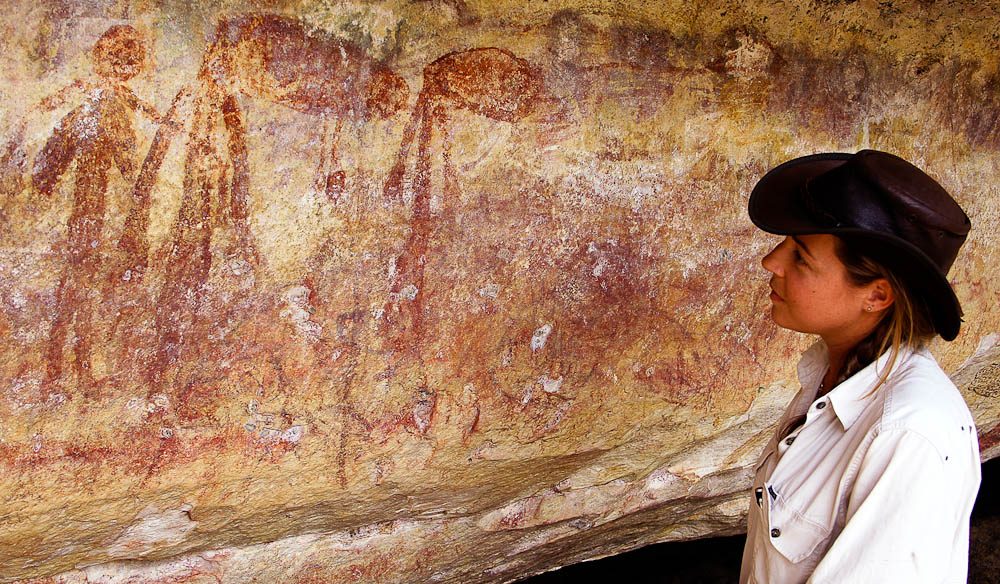

Davidson’s Arnhem Land Safari’s senior guide Clare Wallwork surveys figures in headdresses.

In 1986 Charlie Mungulda, senior Indigenous owner of the Ulba Bunij clan, asked former buffalo hunter Max Davidson to open a safari camp to show a select few white folk his country.

The camp at Davidson’s Arnhem Land Safaris, NT

Davidson and his guides have found more than a dozen rock art galleries that archaeologist Josephine Flood describes as “unrivalled in terms of artistic quality, quantity, colourfulness and excellent state of preservation.”

Mount Borradaile is magical. The art in the rock shelters tells stories that plumb tens of thousands of years in a landscape that still brims with crocodiles, barramundi, and courting brolgas. It feels like you have pierced the curtain of the 21st century and returned to prehistoric times.

Discovering rock art at Mt Borradaile’s catacombs.

“It’s so pristine yet Indigenous Australians lived here for thousands of years,” says Wallwork. “Aboriginal groups worked within the environment yet we Europeans seem to work against it. Everywhere you walk it feels like they left only yesterday.”

“Rock art offers a window into the past,” says Professor Paul Tacon, Chair in Rock Art Research at Queensland’s Griffith University.

“It is all about the history of human experience and the imaginative telling of stories. It shows everything from what extinct animals looked like to how climate change impacted social life.”

Arnhem Land’s Mount Borradaile houses some of the best Indigenous rock art around.

For traditional owners, the art tells the story of their country and their culture. More important than the paintings themselves, which are often superimposed on each other, the act of painting connected Aboriginal artists with their creation ancestors.

“Australian rock art is so remarkable firstly because there is so much of it,” says Professor Jo McDonald, director of the Centre for Rock Art Research and Management at the University of Western Australia. “Australia is unique because its entire occupation was by hunter gatherers and this history is beautifully recorded in the rock art.”

She adds, “The French promote their relatively few sites, such as Lascaux (whose art dates back 20,000 years), as part of their cultural identity. Australia has 100,000 known sites with incredible diversity and complexity yet few Australians know much about them.”

Indeed, the enormity of the legacy of Aboriginal culture – its complexity and spiritual depth – is barely understood by most of us. From finger scratching deep in the Nullarbor caves and coded petroglyphs on the Burrup Peninsula to the vast swath of rock paintings across the continent, every type of artistic endeavour practiced by ancient cultures has been produced here.

“The detail, freshness, range of colour and age of Australian rock art make it unequalled worldwide,” says Cambridge PhD, Jamie Hampson, who recently moved to the UWA Centre for Rock Art Research + Management because, “as an archaeologist with an anthropological approach to rock art, Australia is a wonderful place to work because there are still Indigenous descendants who can provide so much cultural understanding.”

In spite of extensive studies, it is still extremely difficult to pinpoint the age of rock art because most organic pigments cannot be carbon dated. A rare charcoal drawing on the Central Arnhem Land Plateau has been radiocarbon-dated to 28,000 years, making it the oldest painting in Australia and among the oldest in the world with reliable date evidence – but the engravings are probably much older.

Davidson’s Arnhem Land Safaris at Mount Borradaile, which can be visited both in the wet and dry seasons, offers a remarkable body of rock art including an enormous rainbow serpent, expansive contact galleries, early naturalistic animals, dynamic figures and X-ray art.

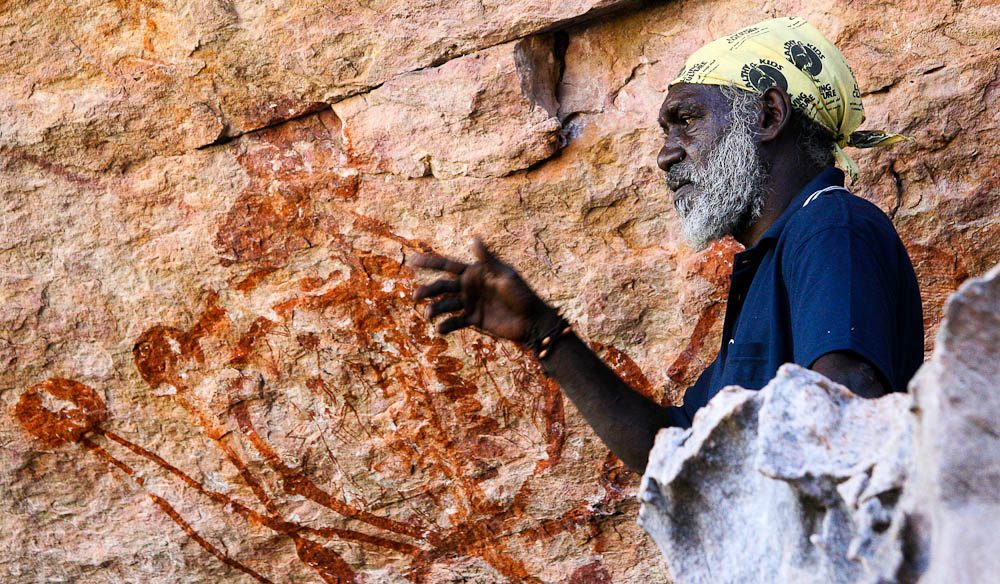

An Indigenous guide at Injalak Hill, also in west Arnhem Land explaining the rock art.

For a complete indigenous experience in Arnhem Land, visit the site of Injalak near the community of Oenpelli where Aboriginal guides describe the stories behind the great variety of paintings at Injaluk Hill.

You can also buy stunning weavings and bark paintings at the art centre. Entry permit required (injalak.com).

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT