For many people, the most visible impact of Cyclone Alfred was the damage big waves and storm surge did to their local beaches.

Beaches in southeast Queensland and northeast New South Wales are now scarred by dramatic sand cliffs, including the tourist drawcard of Surfers Paradise.

Sand islands off Brisbane – Bribie, Moreton and North Stradbroke – protected the city from the worst of the storm surge. But they took a hammering doing so, reducing their ability to protect the coastline.

The good news is, the sand isn’t gone forever. Most of it is now sitting on sandbars offshore. Over time, many beaches will naturally replenish. But sand dunes will take longer. And there are areas where the damage will linger.

Why did it do so much damage?

Cyclone Alfred travelled up and down the coast for a fortnight before crossing the mainland as a tropical low. On February 27, it reached Category 4 offshore from Mackay. From here on, the cyclone’s intense winds whipped up very large swells.

By the time the cyclone started heading towards the coast, many beaches had already been hit by erosion-causing waves. This meant they were more vulnerable to storm surge and further erosion.

As Alfred moved west to make landfall, it coincided with one of the year’s highest tides. As a result, many beaches have been denuded of sand and coastal infrastructure weakened in some places.

UNSW Water Research Laboratory

Which beaches were hit hardest?

Areas south of the cyclone’s track have been hit hardest, from the Gold Coast to the Northern Rivers.

Some beaches and dunes have significantly eroded. Peregian Beach south of Noosa has lost up to 30 metres of width.

Erosion cliffs, or “scarps”, up to 3 metres high have appeared on the Gold Coast. It exposed sections of the last line of coastal defence – a buried seawall known as the A-line, constructed following large storms in the 1970s.

Up and down the Gold Coast, most dunes directly behind beaches (foredunes) have been affected by storm surge of up to 0.5 metres above the high tide mark and eroded. Even established dunes further inland have been eroded.

Javier Leon, CC BY-NC-ND

Where did the sand go?

In just a week, millions of tonnes of sand on our beaches seemingly disappeared. Where did it go?

Beaches change constantly and are very resilient. As these landforms constantly interact with waves and currents, they adapt by changing their shape.

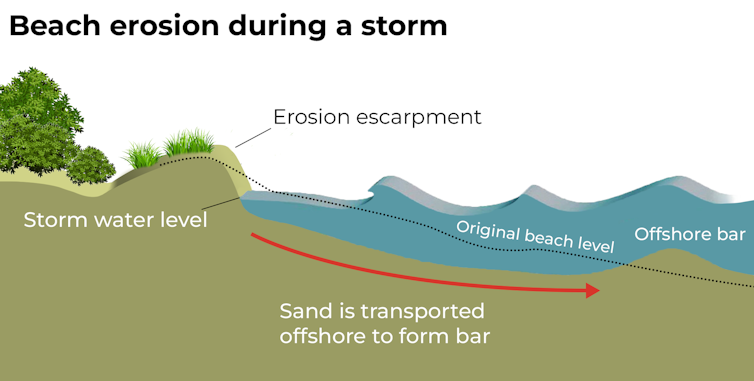

When there’s a lot of energy in waves and currents, beaches become flatter and narrower. Sand is pulled off the beaches and dunes and washed off offshore, where it forms sandbars. These sandbars actually protect the remaining beach, as they make waves break further offshore.

Dunes form when sand is blown off the beach on very windy days and lands further inland. Over time, plants settle the dune. Their roots act to stabilise the sand.

Healthy dunes covered in vegetation are normally harder to erode. But as beaches are washed away during large storms and the water level rises, larger waves can directly attack dunes.

The tall erosion scarps have formed because dunes have been eaten away. In some areas, seawater has flooded inland, which may damage dune plants.

Most sand will return

As coastal conditions return to normal, much of this sand will naturally be transported back ashore. Our beaches will become steeper and wider again.

It won’t be immediate. It can take months for this to occur, and it’s not guaranteed – it depends on what wave conditions are like.

Some sand will have been washed into very deep water, or swept by currents away from the beaches. In these cases, sand will take longer to return or won’t return at all. Dunes recover more slowly than beaches. It may take years for them to recover.

Australia’s east coast has one of the longest longshore drift systems in the world, where sand is carried northward by currents to eventually join K’Gari/Fraser Island.

Can humans help?

Sand will naturally come back to most beaches. It’s usually best to let this natural process take place.

But if extreme erosion is threatening buildings or roads, beach nourishment might be necessary. Here, sand is added to eroded beaches to speed up the replenishment process.

Other options include building vertical seawalls or sloping revetment walls. These expensive methods of protection work very well to protect roads or buildings behind them. But these engineered structures often accelerate erosion of beaches and dunes.

We can help dunes by staying off them as much as possible. Plants colonising early dunes are very fragile and can be easily damaged. Temporary fencing can be used cheaply to trap sand and help dunes recover. Re-vegetating dunes is an efficient way of reducing future erosion.

How can we prepare for next time?

The uncertainty on Cyclone Alfred’s track, intensity and landfall location kept many people on edge, including at-risk communities and disaster responders. This uncertainty puts many scientists under enormous pressure. Decision-makers want fast and clear information, but it’s simply not possible.

In Australia, almost 90% of people live within 50km of the coast. In coming decades, the global coastal population will grow rapidly – even as sea level rise and more intense natural disasters put more people at risk.

As the climate crisis deepens, rebuilding in high-risk areas can create worse, more expensive problems.

Communities must begin talking seriously about managed retreat from some areas of the coast. This means not building on erosion-prone areas, choosing not to defend against sea incursion in some places and beginning to relocate houses and infrastructure to safer heights inland.

Decision-makers should also consider deploying nature-based solutions such as dunes, mangroves and oyster reefs to reduce the threat from the seas.

Technology has advanced rapidly since Cyclone Zoe made landfall in this region in 1974. We can track weather systems from satellites, get up-to-date weather and wave forecasts on our phones and use drones to see change on beaches and dunes.

But these technologies only work if we use them. The Gold Coast has the world’s largest coastal imaging program. But most other coastal regions don’t conduct long-term monitoring of dunes and beaches. Without it, we don’t have access to data vital to protecting our beaches and communities.![]()

Javier Leon, Associate Professor in Physical Geography, University of the Sunshine Coast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT