20 February 2025

![]() 11 mins Read

11 mins Read

Tears fill my eyes as the plane descends towards the Cocos Keeling Islands. Never has a destination stirred such a profound reaction in me. From above, the islands seem to float in the water like green jewels, surrounded by an ocean so blue it looks surreal. Even before we land, this small but glorious archipelago has already taken my breath away.

The palm-fringed atolls are mere specks in the middle of the Indian Ocean that, as well as being incredibly far-flung, feel like an untouched paradise. Sitting almost perfectly halfway between mainland Australia and Sri Lanka, and just south of Indonesia, getting here is where the adventure begins.

Reaching the islands, which are an Australian territory, requires a flight from Perth International Airport, stopping en route at Learmonth on the northwest coast of WA before continuing to Cocos and, eventually, Christmas Island. It’s a journey that feels like a pilgrimage to the very edge of the Earth, and I am immersed in the tranquillity of island life the minute I step off the plane.

A colourful local home on Home Island. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

Cocos is made up of 27 coral islands, with only two – West Island and Home Island – inhabited, forming two distinct atolls. West Island is the administrative and tourist hub, while Home Island is where most of the Cocos Malay community lives. Its remoteness makes it a haven for travellers like me, who are drawn to places where natural beauty thrives and life moves at a slower pace.

White terns are resting in palm trees. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

This isolation creates a sense of serenity unlike anywhere else I have ever been. There are no shopping centres, restaurant chains or crowded beaches here, just miles of undisturbed natural beauty, turquoise waters and powdery white sand. It is the kind of place where your mind can wander, your body can relax and time seems to stand still.

The Big Barge Art Centre is a renowned art space on the island. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

You will find Direction Island just north of Home Island. It’s home to a famous rip, where you enter the water at one end and float its entirety while spotting amazing marine life along the way. A public ferry travels to the island on Thursdays and Saturdays. But you need to bring all your food, drinking water and snorkelling equipment with you due to its remoteness.

The islands are uncrowded and wildly beautiful. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

Direction Island is also known for its historical significance, as it played a key role in the First World War when the German cruiser Emden was destroyed just off its coast. There is a memorial on the island, which serves as a quiet reminder of the battles that once raged in these peaceful waters.

The paradisiacal beaches are all white powdery sand and swaying palm trees. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

I spend some time wandering the island’s trails, which lead me through groves of coconut palms and past the old telegraph station, another nod to its strategic importance in the past.

The Cocos Keeling Islands are named after the coconut trees that grow here in abundance. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

Exploring the Cocos Keeling Islands is a journey best experienced on the water, where each tour provides a new perspective of the two atolls’ marine world. After my adventure on Direction Island, I am eager to explore more of the islands, and the motorised canoe tour with Cocosday is the perfect way to dive deeper. The tour leaves from West Island bright and early, with the lagoon as still as glass. The first stop is Pulu Maraya, a small, uninhabited island that looks like it has been plucked from a postcard.

Basket-weaving is part of the Home Island Cultural Tour. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

I slip into the water with my snorkel on and begin to float down the stream, mesmerised by the coral gardens alive with colour and movement. The coral reefs are pristine and largely untouched by mass tourism, making them some of the best-preserved in the world. Our next stop is a tiny island called Pulu Belan Madar, another uninhabited speck in the lagoon.

Pulu Belan Madar remains uninhabited. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

This stop is all about relaxation. Lying on the soft sand, I soak in the sun’s warmth. Our guides, Scarlet Walker and Hayden Michie, bring out cold drinks and a picnic of fresh fruit, banana bread and dips. As we sit watching the waves gently lap the shore, it is the perfect moment of calm. On our way back towards West Island, a handsome green turtle pops up, topping off a wonderful day.

Cocos is made up of 27 coral islands, including Home Island. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

Another must-do is the glass-bottom boat tour with Cocos Blue Charters. Peter McCartney, known to us as Captain Pete, is a local legend and tailors his tours to your group’s interests, allowing you to snorkel, fish or simply soak in the views of the underwater world beneath you. He takes us back to Direction Island to conquer the rip again, this time on a non-ferry day, so there isn’t another soul in sight.

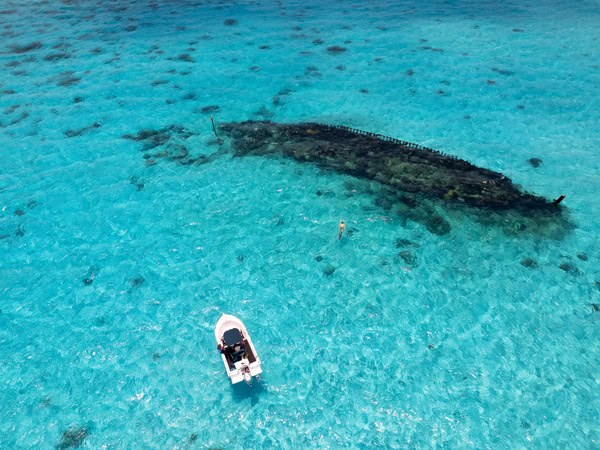

Snorkelling shipwrecks with Cocos Blue Charters. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

We make a few stops on the way back to swim with manta rays and hopefully dolphins. The manta rays are a graceful success, gliding below us like shadows. Dolphins are next on the list. I am excited, but the thing about dolphins is, they often travel with sharks… So, as I put my fins on at the back of the boat, legs dangling in the water, Pete suddenly says, “Oh, there are sharks there!” to which I reply, “I think they’re dolphins!”

Clear water is perfect for underwater photography. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

And as it turns out, we are both right – there are dolphins, but what I had not noticed were the reef sharks lurking just beneath them. Reef sharks are generally harmless, but Pete’s casual warning about how they “sometimes act out” in open water is enough to have me yanking my legs out of the water.

Boat tours explore outer islands and reefs. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

While the Cocos Keeling Islands’ beauty is unparalleled, its cultural and historical significance is equally captivating. The islands were first sighted by British sea captain William Keeling in the early 17th century. But it was not until 1826 that English merchant Alexander Hare arrived.

The islands are covered with lush palms. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

Soon after, in 1827, Scottish trader Captain John Clunies-Ross arrived with his family and a group of Malay workers to establish a settlement. Clunies-Ross declared himself the ‘King of the Cocos’ and turned the islands into his own personal fiefdom, establishing a monarchy that would last more than 150 years.

Inside The Big Barge Art Centre you’ll find local arts and craft. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

Though the Clunies-Ross family’s reign was often romanticised as a benevolent monarchy, the reality is more complex. The Cocos Malay people lived in a paternalistic system where they were paid in company currency, only useable in Clunies-Ross stores, and were bound by strict social rules imposed by the family. This created a highly stratified society, with the Clunies-Ross family enjoying European comforts and luxury while the Malay community worked long hours in the coconut plantations.

Coconuts grow abundantly on the island. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

The winds of change began to blow in the mid-20th century, when the Cocos Malay people started to challenge their status and sought recognition and rights. The Australian government at the time began to take notice, particularly as global views on colonialism and feudal systems shifted after the Second World War.

Walk past groves of coconut palms. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

In 1955, the islands were officially transferred to Australian control, but the Clunies-Ross family was allowed to continue their reign until 1978 when the Australian government purchased the islands from them. The final chapter of the Clunies-Ross dynasty came when the last ‘king’, John Cecil Clunies-Ross, was forced to sell his home, Oceania House, and relinquish the last vestiges of his family’s control over the islands.

Meet local coconut farmer, Tony Lacy. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

Walking through the islands now, it is hard to imagine it was once a kingdom ruled by a single family. But visiting Home Island is a fascinating insight into the Cocos Malay way of life. Traditional Cocos Malay culture is alive and well here, with Islamic influences seen in the architecture, clothing and religious practices. The locals are incredibly welcoming, and I feel like I have been invited into a close-knit community that is both proud and protective of its heritage.

Basket weaving with palms. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

One of the highlights of my visit is joining a cultural tour with Osman ‘Ossie’ Macrae, a local guide whose storytelling brings the islands’ history to life while we feast on a traditional Cocos Malay lunch. Ossie’s deep knowledge and passion for Cocos Malay culture make the past feel palpable.

The Cocos Malay people engage in traditional basket weaving. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

Life on the Cocos Keeling Islands is refreshingly simple. There is a distinct lack of commercialisation, and I quickly adapt to the slower pace. On West Island, the rhythm of daily life is dictated by the tides.

Island life is refreshingly simple. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

Dining options are limited but delightful. The few restaurants and cafes on West Island rotate their opening hours, and it is not uncommon for staff to close shop unexpectedly if the surf or fishing conditions are particularly good. A highlight of dining here is the abundance of fresh, locally caught seafood, all prepared with an island twist.

Visitors can tour the Wild Coconut Discovery Centre. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

As my time on the Cocos Keeling Islands comes to an end, I cannot help but reflect on how this place has touched me, just as it did when I first laid eyes on it from the plane. From the quiet beauty of its beaches to the fascinating layers of its history, the islands leave an imprint. There is a stillness here that you cannot find in many places; a sense of peace that comes from being far away from the noise of the world.

Sitting in the middle of the Indian Ocean, Cocos holds its history close while offering its beauty to those who visit. I leave feeling something I rarely experience when I travel – like a part of me has stayed behind.

Swing into island time. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

Virgin Australia flies to the Cocos Keeling Islands from Perth/Boorloo’s International Airport on Tuesdays and Fridays. The flight time is about six hours and includes a stop at Learmonth, near the town of Exmouth, and continues to Christmas Island afterwards. The flight leaves from the international airport, so make sure you allow extra time to get through customs and check-in.

Stay in an air-conditioned bungalow at The Breakers in the heart of West Island. Rooms are $310 per night for a minimum of three.

A cosy room at The Breakers. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

Cocosday runs a four-hour motorised canoe tour of the southern atoll lagoon and islands for $170 per person. If there is only one tour you book while on the Cocos Keeling Islands, make sure it is this.

Book a motorised canoe tour to witness pristine coral reefs. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

Cocos Blue Charters operates a half-day glass-bottom boat tour for $200 per person. The boat fits four guests and offers shade. When visiting Home Island, book Ossie’s Cultural Tours for $85 per person to learn about the culture and history of the islands over a homemade Cocos Malay lunch.

Join a cultural tour with Cocos Malay local Ossie. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

The locally run restaurants on West Island often alternate their opening hours, so you should be able to find at least one venue open for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Check the visitor centre for updated information. Add your name to blackboards out the front of each restaurant to make a tentative reservation.

Enjoy homemade sweet treats at Sula Sula Servery. (Image: Cocos Keeling Tourism/Rachel Claire)

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT