16 June 2022

![]() 12 mins Read

12 mins Read

Its twisted old trunk is gnarled, its disembowelled carcass plump with cement and now, like many outback legends, its cadaverously pale and very dead. It has stood, an unmolested leafy sentinel, over Barcaldine’s Railway Station depot since the 1880s. It was a living Australian Labor Party memorial and heritage-listed. The double centurion, Oak Street’s most senior resident, was respectfully nursed into its dotage by Barcaldine’s faithful. Countless thousands of travellers photographed it, patted it and peered up at its bushy green tops with dutiful reverence.

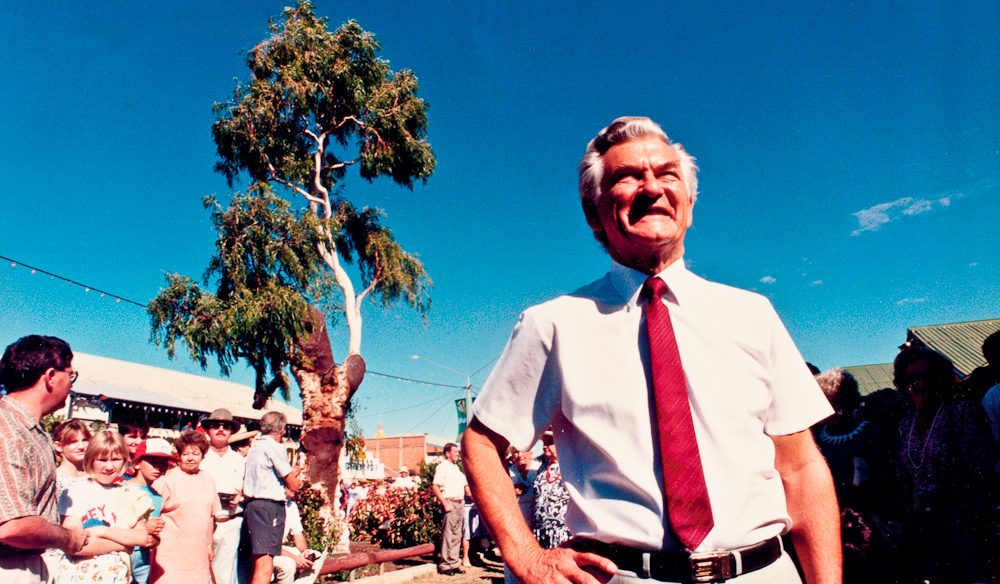

No lesser Labor luminary than the silver bodgie himself, Robert Lee Hawke, embraced The Tree and took home some family snaps for the album. And then, by an act of craven foul play, it was murdered. Allegedly. Cold, hard forensic science pronounced death by poisoning. Sometime around May Day 2007 they reckon. Other more prosaic mourners think the arthritic old gum died of shame.

It didn’t ask to be iconic and could easily have wound up as firewood to heat a billy or bake a damper, but for the fact that under its cooling shade the Australian workers rallied and the ALP was formed after the ramifications of the great shearers strike in 1891.

The wealthy, wool-producing, fat cat squatters ignored union entreaties for living wages and tolerably humane working conditions. Shearing was even harder yakka back then; the shearers were grimly determined to hold out. The conservative government of the time backed the pastoralists to the tune of 1000 armed soldiers. Eventually the wallopers arrested the strike leaders who faced the beak in Rockhampton and were locked up in the hellhole of St Helena Island, just off the coast of Brisbane in Moreton Bay, for three years of cruel, hard labour. Practically a death sentence.

On June 20, 1899, their resources expended and morale destroyed, the unions capitulated. The strike was reluctantly declared over. Ironically, in 1892 democracy struck back and a shearer, one Tommy Ryan (who’d been arrested and acquitted), was elected to the seat of Barcoo – thus becoming Queensland’s first Labor Parliamentary rep. The world-first Labor Government came to power in Queensland in 1899 and eventually the tree was immortalised. It became a pilgrimage for Australian workers. The faithful christened the flourishing trunk The Tree of Knowledge.

A hundred kilometres west up the arrow-straight, road kill-littered Landsborough Highway, a stocky troubadour is prodding his campfire into a satisfyingly frisky blaze. From a case he produces a guitar and, with work-thickened fingers, tunes up. His ruddy, cherubic face breaks into a bewhiskered smile as he welcomes the transient population of the Gunnadoo Caravan Park to his impromptu stage.

It’s a balmy evening in Longreach, pastoral hub of the central west. The sun dissolves. The stars emerge. The freshly showered and barbequed travellers drift around clutching XXXX tinnies and Bundy and cokes to swap travelling anecdotes. (“Mate, I spiked three bloody tyres just getting here.” “Is that all? I got a roo through me windscreen”.) Pyjama-clad kids crouch under tables to giggle and nudge each other. Grasshoppers flit about in the firelight and crash among the cheese dips and sticky lamingtons. The show’s about to go on.

Tom McIvor extracts a stubbie from his guitar case, slakes his thirst with a deeply satisfying draught and strums a chord. The chatter ceases and with a final phssst of broached stubbies and a chorus of shushing, the expectant travellers settle. “Good evening, folks,” beams the balladeer. “My name is Tom McIvor.”

For the ensuing couple of hours, as the smoke drifts aromatically and sparks flit from the glowing embers, the chubby bush poet, songster and purveyor of silly stories enchants his transient audience with impassioned and colourful lyrics that describe life “of the real Australians and the real Australia.” He’s a bushie, and a proud Labor man to his toecaps. He left school early for a life of hard graft. “Best thing that ever happened to me,” he reckons. He loved his folks dearly and was imbued with a strong work ethic. His esteemed father, Tom snr, was “a gentleman” and survivor of 114 professional lightweight bouts, winning 104 of them. A tough way to make a quid in those days. His mother Mary Joan he adored.

A series of dreary jobs followed – pie truck driver, wool scourer, more successfully an apprentice butcher – but his love of horses developed into a 20-year career in rodeo being stomped on by large angry bulls. He proudly maintains that he never broke a bone but “got dropped on me head a few hundred times. But it never affected me.” So saying, he ineffectually empties the dregs of a crisply cool stubbie into his whiskery ear.

He earned, from his bucking good mates, a reputation for being fearless. Or, should that be reckless? McIvor grins modestly and doesn’t disagree: “I’d cut up bulls all week and go ride ’em at the weekend. I’d just swap a steel mesh glove for a leather one.”

He composed songs and verse while nursing bruises and lumps, a badge of honour on the rodeo circuit. He loved every minute of it. His lyrical career began by writing racy ditties after discovering as a kid that he could make people laugh. He morphed into an entertainer, penning rodeo songs while on the circuit. He learned his art from travelling country musos and was discovered and recorded in the US before his own country embraced him. He’s since been recorded by 100 other country artists and has a swag of his own CDs.

He’s a seven-time Queensland Bush Balladeer, has been lauded by the Tamworth Songwriters Association and was declared Song Maker of the Year a decade ago in appreciation of his lifetime’s body of work. He has a plinth on a Tamworth rock to prove it. He swells at the thought. “My pride and joy,” he confesses and pretends to blow his nose. He’s an emotional bloke and wears his pride in being an Australian proudly and lyrically on his sleeve. But pushing 60 has slowed him down a tad, although he’s lost none of his enthusiasm for his art. He performs 180 shows back-to-back in a season. He doesn’t charge, but passes a tin German Army Shultz helmet around after each gig. “We can get 450 vans a night,” he says. “No wonder I feel a bit buggered by the end of the season.”

He spends six months of the year squatting in his hut at the Gunnadoo, performing, writing songs, fishing and best of all slurping stubbies. The other six are spent with his missus, Eve, on Queensland’s southeast corner. “Where else could I do all these things I love doing most?” enthuses McIvor, nodding towards an endless horizon. “I just love the silence and the lack of hassle. People still have time for a chat out here.

“I’ve always loved the bush and the people. I always feel reborn after I leave and head for my regular gigs at Tamworth, my spiritual home,” he explains. Unsurprisingly, his heroes are the likes of Slim Dusty, Tex Moreton and Stan Costa. Tom feels privileged to be able to write authentic songs about genuine country people, their dreams and hardships, and his particular heroes: Australia’s fighting men. He makes no apologies for eulogising the Diggers and inevitably mists over when revisiting their memories in song and verse. His granddad was a Gallipoli veteran and light horseman. “He was one of the lucky ones,” quips McIvor sardonically. “He only got his shoulder blown off.”

His great uncle William defiantly survived the battles, only to be shot and killed by a sniper on Armistice Day. “We have the saying ‘Lest We Forget’,” says Tom. “Well, I’m not going to let anyone forget. No way in the bloody world.”

On one Sunday in every month, McIvor travels the 100km east to Barcaldine, famed – if for nothing else – for its geriatric little gum tree. He breaks out his guitar and the inevitable stubbie and performs beneath The Tree. He does it in memory of his father, who lived in the trim little pastoral town once made wealthy by the wool and the sweat off men’s backs. McIvor admits to being heartsick at the sight of the skeletal remains of The Tree, and turns puce with suppressed anger at the atrocity. “That tree was never vandalised, or in any way defiled,” he says. “Until now.”

Angry and upset over The Tree’s untimely demise at the hands of “some bastard,” McIvor has immortalised the bleached and woody corpse in song. “I always wanted to write a song while it was still alive,” he fumes. “But now The Tree has been taken from us. Now it’ll become a eulogy.

“I ALWAYS WANTED TO WRITE A SONG WHILE IT WAS STILL ALIVE. BUT NOW THE TREE HAS BEEN TAKEN FROM US. NOW IT’LL BECOME A EULOGY”

He draws an analogy between the now very ghostly gum and another great Australian morale booster; one that galloped into legend and the Australian psyche – the huge-hearted and hoofy champion, Phar Lap.

“Phar Lap drew a nation together just as the tree has done,” says Tom. “And both have suffered a mysteriously similar fate. Both were killed with a lethal dose of poison.”

Forensic evidence has declared that The Tree was indeed poisoned to death. McIvor has a more wistful theory: “I personally reckon The Tree died of shame. It seems strangely coincidental that the day Little Jonnie Howard announced his shameful IR laws that the tree began to succumb.

“I think the dead tree will become more famous than the living one,” predicts McIvor ironically. He thumps the table with considerable force, upsetting the forgotten stubbie and startling a small flock of nectar feeders (and me) lurking among the shroud of crimson bougainvillea shading the Commercial Hotel’s beer garden.

“It was a shrine for the working men and women and I think John Howard will be in hell for a long time for what he’s done to this country.”

He lifts his guitar and, unashamedly teary eyed, begins his heartfelt lament:

They were worked like dogs and treated worse for a pittance from the squatters’ purse, who somehow felt superior because he thought his blood was blue. But the blood of those good men he killed made the shearers iron-willed, and they stood together proud and strong like true Australians do.

It stood a silent sentinel through fire and flood and drought. It’s heard men cry, it’s seen men die, it’s heard the victory shout. And it’s seen hard-fought conditions stripped away as years went by, as a nation stared in disbelief and watched her branches die.

Oh, they brought in all their experts to try and save our tree. A symbol of our heritage that set our workers free. Some say that it was poisoned and they tried to place the blame. But the IR laws have been the cause and the old tree died of shame.

Did the old tree die of shame?

Beneath that grand old ghost gum that looks so stark and bare, tourists click their cameras and I’m sure they really care. You can see the teardrops glisten at the ghost that she became, and they tell their grandkids all about the tree that died of shame.

Oh, the tree that died of shame.

The show is over. McIvor quietly replaces his guitar, mounts his battered old Falcon wagon and vanishes up the Matilda Highway for the peaceful and shady banks of the Thomson River. He’s going fishing.

The good burghers of Barcy weren’t about to have their eldest and most celebrated resident wind up as firewood for searing acacia-flavoured chops atop someone’s Sunday arvo barbie or – worse yet – flogged off as souvenirs. The town rallied. Yeppoon-based architect Brian Hooper was promptly engaged to design a suitable memorial for the tree’s toxic corpse. Dismembered and packed off to Brisbane for mummification, its torso and bones will return and be reunited – phoenix-like – with the locals. The veneration of the trunk and its three skeletal limbs will scrub up to $5.1m. That’s real expensive barbie fuel.

Obligingly, McIvor provides this story’s punch line. As the trunk was gently lifted free and surgically dissected into more manageable body parts, McIvor chorused his anthem from the nearby pavement, shaded by the verandahs of the Artesian Hotel, a refreshing stubby comfortably at hand. Later, as the crowd drifted away, he spotted an excited bloke filching a shrivelled skerrick of the tree’s poisoned root. “Hey, mate. Have a look what I’ve got,” the grave robber boasted, brandishing his trophy under the balladeer’s bristly nostrils.

“Mate, that’s amazing,” admired Tom. “It’s not every bloke that can pick up a root around here on a Sunday morning.”

WHERE // Around 520km west of Rockhampton, Queensland.

GETTING THERE // Buses operate daily from Brisbane, The Spirit of the Outback train arrives from Brisbane twice a week, and QantasLink flies daily from Brisbane and Longreach.

CONTACT // Barcaldine Tourist Information Centre: (07) 4651 1724

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT