02 August 2023

![]() 13 mins Read

13 mins Read

One solitary rock is all that it takes to unleash it. Just a seemingly benign souvenir, from a landscape with billions of such specimens, carelessly plopped in your pocket and forgotten about. Forgotten about, that is, until it comes knocking.

What is it? Hard to say, exactly. Cynics say it’s a steaming pile of hocus-pocus doo-doo. But then there are the believers; reluctant converts to the idea of the inexplicable, nebulous curse known as ‘Karijini Karma’.

What do we know about it? It’s OK simply to pick up a rock in Karijini National Park, let its iron dust tint your palm; run your index finger along its sharp edges. A paper trail of regret and repentance tells us that this primordial can of whoop-arse opens up only when said rock leaves this sacred national park’s bosom.

“I receive packages in the post from all over Europe, America and Asia, plus every state in Australia, containing rocks from visitors who removed them during their stay,” says Karijini’s Kennedy-jawed senior ranger Dan Petersen, from under a sweat-stained hat that looks like it’s been snacked on by a dingo. “Usually there’s no name or return address but just a note saying: ‘Dear Ranger, I removed this rock from the park and have had nothing but bad luck ever since. Please put it back’. Some have mud maps of where the rock was taken from, so it can go back to exactly the same spot.”

After an impulsive career change five years ago flung him north into the West Australian outback, Dan has come to know Karijini as well as any white man can. “There’s an energy that runs through this place,” he says. “It got into me straight away.” Some say Dan wears a khaki cape with a big D on it under his ranger’s shirt. On his days off, just for kicks, he trawls Google Earth to discover the “less discovered” places in the gargantuan park’s remote south. He grabs his backpack, a compass and strides out into the remote wilderness (solo) for five days at a stretch. Luckily, Dan’s the kind of outback superhuman who can eat grass in the unlikely scenario that he can’t source water.

“I sometimes see random lights in the night sky out there, which move really quickly,” Dan says. “In some places, it feels like you’re the first person who’s been there for thousands of years. The wildlife out there don’t have the fear. They come up and sniff you.”

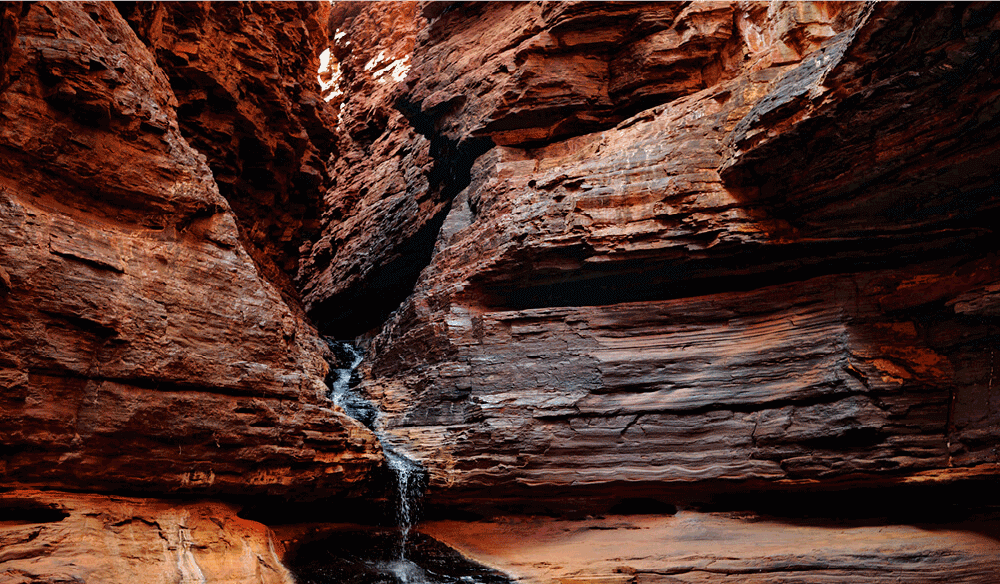

Luckily, you don’t need Dan’s superpowers to access Karijini’s superstars: a medley of bewitching gorges that dramatically and unexpectedly fall from the flat, baked earth into an antediluvian waterhole-strewn realm, daubed with such unlikely contrasting colours that it makes your brain hurt.

Despite the impossibility of hues in the gorges, most people in the outside world only see one colour in the Hamersley Range; you see, Karijini sits in the guts of iron-ore country, the backbone of the Pilbara, where rusty red blankets the landscape like outback snow. Amateur geologist (at the time) Lang Hancock saw an inland sea of dollar signs when he flew over the Pilbara’s escarpments for the first time in the middle of last century. That flight, of course, led to mass mining in the area around Karijini and beyond; the windfall still resonates in his daughter Gina Rinehart’s bank accounts today.

Crossing the tracks from mining country to the scared country of Karijini (photo: Jonathan Cami).

Right on Karijini’s boundary is Marandoo mine. And 60 kilometres to the west is Rio Tinto mega-mining town Tom Price (WA’s highest town), which has a tight long-term community of resident miners, and infrastructure enough to host the area’s battalion of FIFO workers, who are more likely to visit Kuta than nearby Karijini.

The hills around town look like an angry sore, which underlines just how important national parks like Karijini are for the next generation of Australians and, indeed, this generation of traditional owners: Banyjima, Yinhawangka and Kurrama peoples. After all, the quirks in Karijini’s landscape were used as meeting places and shelter long before humans really even knew what to do with iron.

While its physical splendour could easily place the national park on the Natural Wonders of the World list (yes, really), what the exquisite images in this article can never convey is the intangible energy and personalities of each and every Karijini gorge. As the bumbling lawyer from The Castle says, “it’s all about the vibe” out here.

Karijini rewards the lively, adventurous traveller; this certainly ain’t the place for a flop-and-drop long weekend. Several of the gorges are fairly easily accessible. Joffre, for example, acts like a backyard swimming pool to the Karijini Eco Retreat, although it still requires a steep walk-in. For the rest, jump in your jalopy and go forth to meet them. While there are a few outstanding lookouts in the park, which offer grand views and perspectives, you truly have to descend to revel in what the fuss is all about.

At the low-key car parks, eucalypts and low mulga woodlands camouflage the gorges with military precision. It’s not until you basically stand on a 100-metre cliff edge that you realise this isn’t just normal pancake-flat outback.

Up on the surface, you won’t see too many large animals hanging out in the midday heat, save for a sun-baking goanna, who suddenly decides to saunter away, with a Straight Outta Compton gait, when she decides you’ve breached her personal space. (Dusk and dawn are best for wildlife watching.) Down below, however, birds inundate the sheltered watercourses like hoodie-wearing youths at a shopping mall.

Watch out for termites (photo: Jonathan Cami).

As you descend the steep marble-strewn tracks and stairs, and leave the tropical semi-desert boiler room behind, the temperature regulates immediately. Spinifex and tenacious desert flowers, such as the ultra violet (when in season) mulla mulla, share the hard ground with unlikely deep green grasses, ferns and, in some places, even fig trees.

From below, Santorini-white snappy gum trunks, which grip doggedly onto canyon ledges, contrast fabulously with the oxidised cliffs and undying cumulus-splashed outback blue sky: a ready-made Benetton ad campaign, if ever there was one.

Each gorge has a distinguishing trademark (or two or three), from the Fern Pool and Fortescue Falls around Dales Gorge; to Kermit’s Pool (take a guess) and the Spider Walk (you have to use both hands and feet to navigate, like Spider-Man) of the magnetic Hancock Gorge.

For anyone with a passing interest in geology, Karijini feels like 2500 million years’ worth of Christmases have all come at once; the exposed banded rock is some of the oldest in the world. Fascinatingly, no actual animal fossils have been found in the older formations here because the layers apparently predate complex animal life.

If you know what to look for, however, you may stumble upon the odd stromatolite in the lower echelons of this former sea floor. The complex dome-shaped algae collection from another aeon is a snapshot of the world’s first recorded life forms. Living examples can still be found at Shark Bay, on WA’s coast.

Once in the gorge netherworld, the conundrum for the truly adventurous is just how far to explore; you always want to stick your neck around just one more bend, and the one after, even when signs tell you not to be so stupid. Three words: Don’t. Do. It.

Rescue times in Karijini are measured in hours not minutes. And there are precedents of thrill seekers having their last thrill here – the spectacular Regan’s Pool is named after an SES volunteer who drowned attempting to rescue someone back in the noughties.

Fret not, adventurers; there is an authorised option to take you deeper. Much deeper. Strap on a helmet, stretch yourself into that wetsuit (lubricant optional), because it’s time to harrumph at the ‘do not enter’ signs with people who know well not only the perils but also the enigmas of these gorges: the crackerjack canyoners of Pete West’s West Oz Active Adventure Tours.

Pete West of West Oz Active Adventure Tours (photo: Jonathan Cami).

Past the signs, a tricky shuffle through Knox Gorge’s deep V underlines why this place is a giant mousetrap for the unprepared and ill-cautious. While not strictly subterranean, with (usually) a thin sky-blue line above lighting the way, sometimes it feels like you’re heading straight down Mother Earth’s oesophagus.

A mouthful of the neutral water quenches like 25 isotonic drinks never could. A chilli-red dragonfly slurps some, too, before it flutters away to wherever chilli-red dragonflies spend their shady afternoons.

Along the streams, more wet seasons than anyone can know for sure have sandpapered the rock surface so much that at one point a narrow section transforms into a slide, and a dog-leg means you’re propelled off a four-metre drop completely blind, into the waiting cool (temperature and ambiance) deep-green pool below. The canyon walls here look like they reach up all the way into the ionosphere.

The novice canyoner has to trust their guide like they would a doctor or pilot. Case in point, the next (seven-metre, again blind) abseil down a waterfall that’s bashed its own exit hole through solid rock.

From above, it looks like you’re headed straight for the mystical Orient, via the Centre of the Earth. Water raps on your helmet like that annoyingly consistent year seven bully. The big outback sky reintroduces itself again at (the no-s***-Sherlock-named) Red Gorge; a logical place to stop, take a few breaths, and hoover up the last of your pre-packed carbs and energy bar thingies.

Upstream, a few-hundred-year-old paperbark is rooted into the flanks of the channel, which obviously hosts ferocious torrents, come wet season. There’s spectral cotton-wool-like foliage in the tree’s upper reaches; its branches like eager hands desperate to scale the gorge walls.

Centuries-old paperbarks survive wild torrents every wet season (photo: Jonathan Cami).

Turns out that it’s not foliage at all, but spider webs, satellite suburbs of arachnids that somehow know exactly how high to reside to avoid being swept away into a Rescuers Down Under sequel. The organic flotsam hanging from this grand old dame’s shoulders is as good a future depth indicator as anything modern science offers.

We plant bums in inner-tubes for a delightfully dawdling paddle up the wide, sunny gorge; then refocus for a scramble through, and (roped) rock climb up and out of, the gorges.

Somewhere, in the canyon depths, we pass by (but not through) an old Indigenous birthing pool, a reminder that this is not just a gigantic outdoor adrenaline junkie theme park, here purely for our pleasure. For the Banyjima people in particular, these gorges are their still-unfolding, living and breathing story.

“We respect each pool,” says West Oz Active’s energetic assistant guide Lauren Pember. “We don’t jump and splash where we can help it, and walk in where possible.” ‘Prone to wander,’ states a tattoo on Lauren’s arm. It’s the unspoken mantra of those who actually live in this isolated park. Super Dan probably has a similar one inked directly onto his soul.

As a temporary home, Karijini National Park has its shortcomings: stuff-all phone reception and supermarket visits that are more quest than outing top the list. “It’s quiet and we go to bed at 9:30pm many nights, but we get to watch the sunset every single day,” says Lauren, who has also called Albania and the Swedish Arctic Circle home. “It’s the most amazing feeling sitting around in awe with absolutely nothing, especially pubs, to distract you. And now that the red dust is in my blood, I couldn’t live in a city. Peak-hour traffic here is like one cow on the road.”

And herein lies the principal challenge for the short-term Karijini visitor. How do you de-tune from your four-walled existence, embrace the elongated sense of time and space, and then re-tune into the park’s wavelength in just a handful of days?

Even tucked into your comfy bed inside the Eco Retreat, your first night might be a little unsettling; especially without the unremitting and reassuring dopamine fixes of phone reception. The desert winds that hit your tent’s walls seem threatening at first; the 3am dingo howls in the distance even more so. Sleep assured though, this is simply Karijini introducing herself.

Rise with the sun (as you inevitably do when glamping anyway) and follow your instincts. Seek out the gorge that most resonates with you; listen to it. Stop and stare, spend time there, especially if you are privileged enough to have it all to yourself.

Evenings above ground in Karijini (photo: Jonathan Cami).

On the surface Kalamina is just another gorge; replete with colourful algae, blushing walls, stepped waterfalls. But for some reason it spoke to Super Dan (and this writer) the loudest. Ironically, it’s one of the park’s most accessible gorges. “When I used to travel near Kalamina, I would feel really uneasy,” says Dan. “So I asked a [Banyjima] elder why the energy down there felt so different. He told me that back in the day there was a huge fight down there. A lot of people died. That tallied with the way I felt.”

But there is nothing to fear, if you respect Karijini. In fact, the park’s energy can be a clarity-giving, revitalising force. “You see it with families,” say Dan. “The first day you can see the anxiety in them, trying futilely for phone reception. Three days later, the kids are covered in red dust, with a stick in one hand and a rock in the other. The kids have become kids again.”

And that’s how you get to know Karijini: breathe it in, accept its challenges, go with its energetic flow. Just make sure to check your pockets on the way back to the harsh, real world. As they say, Karma’s a bitch. That’s if you believe in stuff like that.

Karijini Eco Retreat, within Karijini National Park, is located off Weano Road, near Joffre Gorge, 80 kilometres north-east of nearest major town Tom Price and 130 kilometres north-east of Paraburdoo airport, which is serviced by Qantas and Virgin Australia flights several times a week.

Karijini Eco Retreat is open year-round and offers campsites from $20 per person per night; eco cabins for up to four guests from $159 to $280 per night and eco tents from $174.50 to $349 per night including continental breakfast, kiosk, licensed bar and restaurant on-site.

UPDATE: As of January 2021, West Oz Active Adventure Tours made the difficult decision to close the business due to the impact of the global pandemic and are no longer offering tours.

Want to know more? Read our Ultimate guide to visiting Karijini National Park.

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT